I am at the bi-annual “New Socialist Initiative” meeting in Hyderabad, Andra Pradesh. I came all the way here with some comrades from Delhi University. Together we constituted the “Delhi Team.” We took the AP Express on a second-class sleeper car from New Delhi Station through Haryana, UP, MP, Maharastra, and finally, thirty hours later, AP.

Apart from discussing the prospects and problematics of a socialist revolution in India and producing a political platform to release to the public, the conference was attempting to navigate its way through the complexities of India’s linguistic diversity, and trying very hard not to hurt anyone’s feelings along the way. There were multiple language groups present at the meeting, speaking Gujarati, Telegu, Hindi, Urdu, English and others. After some deliberation on the first day, the conference committee (made up mostly of Hindi speakers) decided that the discourse of the meeting would be limited to Hindi, Telegu or English, or some combination thereof. There would be subsequent translations in the other two languages for each speaker, each question asked from the house, and each answer given in response.

The NSI meeting has got me thinking about different language-based public spheres in India. By traveling from Delhi to Hyderabad, we were also entering into a different kind of public sphere, one in which Telegu was the predominant language. Does the language of public discourse shape how a particular public takes form? This is an interesting question to pose in a country with no less than twenty-eight different states, most of them segmented on the basis of language. Underlying the whole debate about conference languages was an unspoken desire not to offend any particular language group, particularly Telegu speakers in their own state. There was a desire not to blindly reproduce the linguistic hegemony of Hindi and English (and they’re hybrid co-creation: “Hinglish”). And yet, despite the best of intentions, the dominance of these two languages would resurface throughout the day’s meeting.

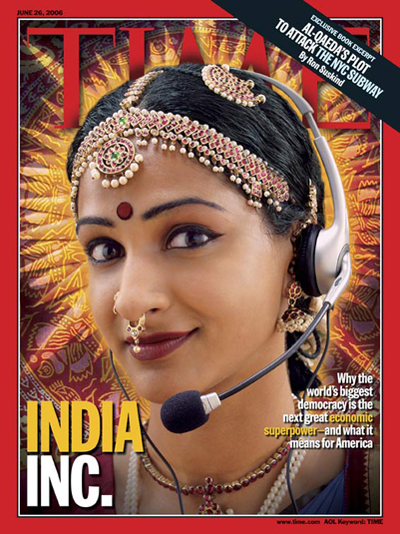

After lunch on the first day I had an “extra special” bidi, and during the afternoon session, one Telegu speaker was making a rather lengthy comment regarding the NSI’s draft manifesto, to be released to the public after discussion of it that afternoon. My thoughts began to drift as soon as I realized that Telegu sounded nothing at all like Hindi, and the rapid fire rhythm of the language set my mind to thinking about Gurgaon’s “Hinglish” speaking public sphere, and the different forms and spaces in which it is manifest. Two contrasting expressions of this public sphere can be found on the web (the virtual public sphere). One is www.gurgaonscoop.com, which is a cyber buzz hub for the “new Gurgaon,” reporting on up-to-the-minute real estate developments, corporate business news, and other predominantly “middle class” issues such as infrastructural inadequacies, new mall and condominium openings, ads for skin-lightening creams, security, and the like.

The second site is https://gurgaonworkersnews.wordpress.com/, which is a blog that depicts a radically different image of Gurgaon. This image is one of labor struggles against exploitation by multinational companies and the exposure of collusion between capital and the state against workers’ rights. Both of these sites are in English.

A few weeks ago, I had a first hand experience with Gurgaon’s more official, “Hindi”-speaking public sphere, at the Additional Deputy Commissioner’s (ADC) office in the Mini Secretariat Building in old Gurgaon. I had made an appointment with Mr. Praveen Kumar a few days before on the phone. Just before our curt conversation abruptly ended, and after I had told him that I was a PhD student researching urban development and planning in India, he asked me suddenly: “Do you know anything about water tables?” Baffled by both the specificity and randomness of this question, I was further confounded by what he said next: “we need someone to help us increase the level of our water table. Do you know anything about water tables?”

I told him I didn’t, and he quickly bade me farewell, “Okay, we will meet at 11 on Thursday,” and hung up. He sounded disappointed in my response.

That night I did some research on water tables in Gurgaon, learning that the table (level of underground water) was rapidly depleting, at a rate of 10 meters per year. In just ten years, I read, Gurgaon would run out of the underground water that had quenched its endless thirst for hundreds of years. Provisions were already underway to transport water from other parts of northern India to feed this thirsty neoliberal city. Little did its middle and upper middle class and perhaps even poorer residents realize all this. Or maybe they had heard about it but did not really understand how it would affect them, or what they could even do about it. The Additional Deputy Commissioner, on the other hand, seemed very concerned.

I reached the Mini Secretariat Building two days later, a very shabby old concrete structure with a circular driveway and some half-assed gardening in the front. It was a busy morning and the space was filled with a bustling kind of bureaucratic energy. There were officials in worn-out suits, and local citizens coming in to file complaints and paperwork with commissioners, town planning officers, magistrates, etc. I was struck by the eclectic crowd that animated this space, ranging from shady-looking businessmen and rich farmers with thick, dark mustaches to more humble-looking villagers and women in colorful saris, with jingling bangles on their ankles.

Looking back, I really should not have anticipated that my meeting with the ADC would begin on time. Not only was this India, but it was local India, bureaucratic India, a million miles away from the privatized gated communities and glitzy shopping malls located just on the other side of National Highway (NH) 8, which cuts the city into distinct hemispheres (roughly dividing “New Gurgaon” from “Old Gurgaon”). But there was no way I could have foreseen just how strange this “meeting” would turn out. Indeed, it was not really a meeting at all. After waiting for half an hour outside his office, one of his peons motioned me in. As I walked in, I saw three rows of chairs lined up before a large, freshly polished wooden desk. It turned out that 11-12pm on any weekday just happened to be the time that the ADC’s office was open to the public, and anyone could come in to take up their personal or village beef with the ADC. The first two rows were full of people in suits and neatly combed hair. ADC Kumar was sitting on the opposite side of the desk, the rich brown colored sea of wood between them bestowing upon the latter a disproportionate heir of authority. On the left side of the room there was a line of chairs that extended along the wall, where rugged-looking villagers were sitting quietly in kurtas and lungis, one or two with dust-stained turbans covering their heads. Everyone seemed to be meeting the ADC at the same time. As I stood watching at the back of the room, I could see that the ADC was carrying on at least three or four conversations simultaneously, registering specific complaints from the villagers seated on the left, while discussing more general urban issues with those seated in front of him. Sometimes he would interrupt someone in mid-sentence to pick up his mobile and start a whole new conversation over the phone. When he finished his phone conversation, he would effortlessly pick up right where he had left off with an existing conversation with in the room. Several peons came in and out at regular intervals, bringing water for his visitors or tea for himself and his crew of “yes men” seated in the front row. This latter group would inject “ha ji’s” and “ore kya’s” in between the ADC’s monologues, which were frequent and quite informative.

“Come sit down in a chair,” the ADC said to me when he finally noticed my awkward presence in the rear. “Let me just finish up these people, I’ll be with you in two minutes. Do you want some chai? Or some orange juice? Vikram! Chai juice lao!”

Mr. Kumar himself was a fascinating character. He was of a slight build, but not diminished in stature. Instead, he had a commanding, fatherly sort of presence, and this was reflected in the way others addressed him, speaking to him with the utmost respect and reverence. He had a neatly trimmed mustache, salt and pepper hair, mid-to-upper-40s; he looked like he could be the proud father of a pretty young school girl or a smart-looking son. His personality was a blend of his constitutive selves: part self-confident Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer (you have to pass a very difficult Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) test in order to become an IAS officer), part patriarch, and part quasi-spiritual guru. Indeed, his language mixed bureaucratic vocabulary and religious talk, “paramathma this, paramathma that…”. He didn’t appear to find any contradiction in using such religious discourse in an ostensibly secular, public space.

The ADC didn’t so much “converse” with the others in the room; rather, he lectured them and called them “beta,” talking to them like a caring, but stern, parent. But he wasn’t necessarily disrespectful to these people either. Instead, he came across as over-nurturing, if somewhat patronizing, whether to middle class suits seated in front, or villagers from more humble backgrounds on the side. He seemed to take his position as ADC as a sort of personal blessing from god, as if it was his enduring faith and not his hard work that had earned him his title. His position as ADC essentially made him second in charge of the district of Gurgaon. His official title was ADC cum District Rural Development Agency, which probably explained why there were so many villagers from the surrounding farm lands in his office.

The ADC’s demeanor suggested that he was good at his job, or at least attempted to get things done. This did not mean, of course, that he was an extraordinary administrator. Indeed, how could he be? He had just been appointed to his post a month before and would probably be shifted to another district before the end of next year. There was a big wooden plaque that hung on his wall on which was engraved the names of the previous ADCs stationed in Gurgaon. I could see that in the past year alone, two different ADCs had come and gone. Mr. Praveen Kumar was the third ADC in 2008.

One of the problems with Gurgaon as an urban administrative space is that its public servants and governmental institutions do not seem to have a stake in the city’s long-term well-being. Haryana Urban Development Authority, which is responsible for building and maintaining infrastructure in Gurgaon, as well as allocating land for private development, is located all the way in Chandigarh, and is in many ways disconnected from the realities of Gurgaon. On top of that, the public administrators themselves serve short appointments and never stay in any one district long enough to see through any changes or longer term goals they might envisage. For these reasons, no matter how skilled or intelligent ADC Kumar might have been, the institutional structure of local and state governance in India seemed to inhibit him from having any kind of meaningful long term impact.

So I didn’t end up getting a personal interview as I had intended, but I did get some freshly squeezed orange juice (a must-have wherever you happen to be in India), and a first hand look at the everyday bureaucratic politics of local Gurgaon. From my third row seat in his office, I quietly observed as the ADC jumped from fantasies of urban improvement with the “yes men” (he told of his desire to purchase several “huge vacuum cleaners” to “suck up the streets” and rid Gurgaon of its perpetual dust problems), to quickly going through the line of village people on the left side of the room. One older gentleman was a Sarpanch from a nearby village, who had come to complain about a water pump that was promised but never installed. Another was a plumber who had been waiting four months for payment from a tight-fisted customer. “Go tell my aid in the outside office, and Paramathma willing, we’ll fix it right away,” the ADC replied in a hurry, and the men quietly exited from the rear.

“In my position, beta, you have to be a jack of all trades,” he said to me, momentarily remembering my presence. But a master of none? I guessed silently. But he wasn’t so modest: “you must have the ability to do whatever is asked of you. From dealing with village problems to developing water tables and constructing roads. Our job is never done.”

* * *

By the time my mind returned me to the NSI meeting, the same Telegu speaker was continuing his diatribe. He was an older man with thick-rimmed glasses, neatly combed hair, and a dark, weathered complexion. I later found out that the man was called Comrade Rao, and he was a former Naxalite fighter and currently a dedicated cadre of NSI.

The extended monologue in Telegu served as an interesting reassertion of the language in this subtly contested multi-lingual space. By that point in the day Telegu had quietly taken a back seat to Hindi and English, with most speakers choosing one of these two languages, or seamlessly switching between them. The subsequent Telegu translation would come almost as an after thought, and many Hindi/English speakers chose these times to clamorously get up and go to the bathroom, drink some water or take chai.

After Comrade Rao had been speaking for nearly half an hour, he was not so subtly asked by the Telegu translating moderator to “wrap up” his point. (Meetings like this are perfect for the “wrap it up” sign from Chappelle’s Show—“Wrap it up, B! Wrap that shit up!) This interruption seemed to upset Rao, and he immediately shrank into his seat and said in heavily accented English, “OK, fine, I finish.”

At that moment I happened to lock eyes with Tara, who was serving as the Hindi-English translator for that session. We exchanged smiles, communicating nonverbally our relief that Comrade Rao had finally finished his statement. I was taken aback by the brightness of her smile. It surprised me that I hadn’t noticed how pretty she was until then.

Tara was from the northeastern Indian state of Assam, living in Delhi and working as a lecturer in English literature at one of the numerous colleges in Delhi University North Campus. On the train ride to Hyderabad, still early in our journey, she got into an altercation with a young man from Haryana who allegedly had used the word “chinky” as she was walking past him in the car. She angrily pointed a finger right into his face, demanding to know why he used that word. The altercation quickly blew up into an all-out yelling and shoving match, with comrades Naveen and Praveen from our group getting into the face of a group of roughnecks’s that took up the young man’s cause. The latter argued that he wasn’t actually talking about Tara, he was referring to his camera as “chinky,” since it was made in China. Tara’s point was that it didn’t matter because the word itself was wrong, but this point got lost in the bravado and aggressive clamor of males on the edge of animal behavior. The two opposing groups of young men continued to yell at each other far after their initial points had been made. After great effort, we were able to stick enough bodies in between the warring clans and things settled down.

I later asked Tara if she got called “chinky” a lot in India. She said she did, even in Delhi, and told me some infuriating stories about the stereotypes and ignorant comments people from Assam and other northeastern states were subject to everyday. Even in a place as eclectic as Delhi, this kind of ignorance and stupidity was widespread. I tried to comfort her and told her about an experience I had when I was a young student in elementary school in rural Pennsylvania. As the only non-white kid in my class, my classmates, knowing no better, used to ask me if I was Chinese (they had apparently never seen neither a Chinese person, nor an Indian, before in their lives). So perhaps ignorance in America wasn’t so different from ignorance in India, I told Tara. She agreed but did not seem particularly comforted by my words. In any case, I respected Tara’s toughness and the fact that she stood up for herself. Moreover, I was grateful that the yelling match didn’t get physical, since a crowded train car twenty-nine hours away from its final destination didn’t seem like the best place to start a brawl.

My eyes were fixed on Tara long after our mutual exchange had passed, and Comrade Rao’s statement was now being translated by her into English. It was a long statement and I will end this wandering post with a fragment from it: “Socialism can never be defeated, it is not something that is even ‘defeatable,’ as such. One attempt at socialism might have failed in the 20th century, but it will always come back again. As long as there is capitalism there is always the possibility for socialism.”